Conflicting advice about protein fills every health forum and gym circle, making it hard to know whom to trust. Sorting science from myth is crucial if you want real results from your workouts, not just empty promises. By breaking down the evidence on optimal protein intake, protein quality, and daily needs, you’ll discover simple strategies to support muscle repair, fuel your energy, and meet any fitness or wellness goal with confidence.

Table of Contents

- Defining Optimal Protein Intake And Myths

- Different Protein Sources And Quality Ratings

- Daily Protein Needs For Active Lifestyles

- Timing, Distribution, And Absorption Factors

- Risks Of Too Much Or Too Little Protein

Key Takeaways

| Point | Details |

|---|---|

| Optimal Protein Intake Depends on Individual Factors | Protein needs vary based on age, activity level, and fitness goals, typically ranging from 1.2 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight. |

| Protein Quality Matters | Not all proteins are equal; choose high-quality sources that offer complete amino acid profiles and consider combining different plant proteins for better nutrition. |

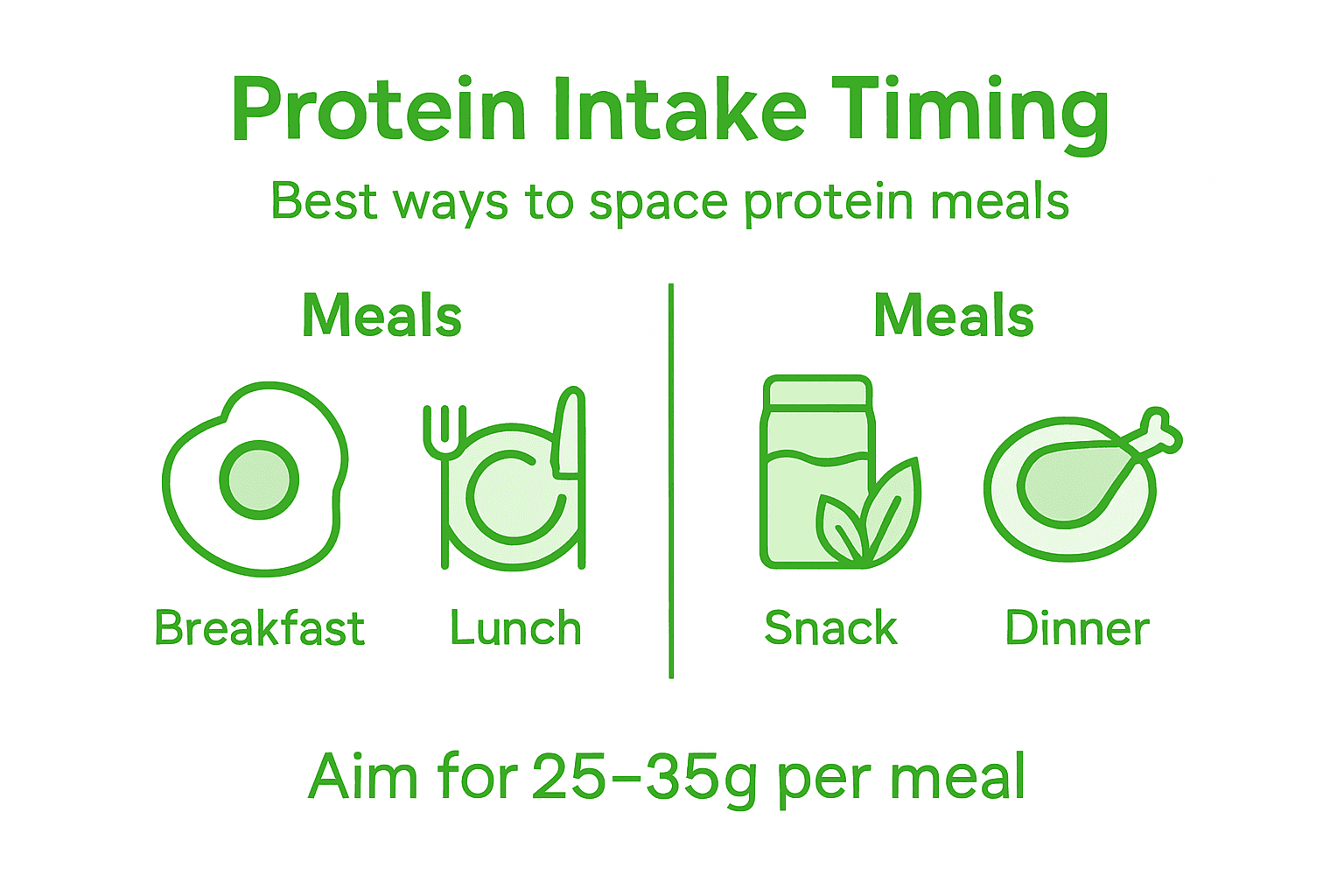

| Timing and Distribution are Crucial | Distributing protein intake across four to five meals enhances muscle protein synthesis; aim for 25 to 40 grams per meal. |

| Balance is Key | Avoid extremes in protein consumption; target optimal intake levels to support health without overloading on protein, especially for healthy adults. |

Defining Optimal Protein Intake and Myths

When you scroll through fitness communities or nutrition apps, you’ll hear wildly different claims about protein. Some swear by the classic 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight, while others insist you need nearly double that. The truth is more nuanced than internet debates suggest. Your optimal protein intake depends on your age, activity level, fitness goals, and overall health status. Rather than chasing a one-size-fits-all number, understanding what the science actually says helps you make decisions that work for your specific situation.

The current dietary protein recommendations from health authorities like the USDA start at 0.8 g/kg/day for sedentary adults, but this baseline may actually underestimate what many people need, especially if you’re strength training or managing aging muscle mass. The disconnect between the Recommended Dietary Allowance and real-world fitness goals has spawned countless myths. One persistent misconception claims that eating more protein automatically damages your kidneys in healthy individuals, a claim that research on protein intake myths consistently debunks for people without pre-existing kidney disease. Another myth suggests protein only matters if you’re building muscle, ignoring the fact that adequate protein supports bone density, immune function, and metabolic health regardless of your workout routine.

Here’s where it gets practical: optimal protein intake typically ranges from 1.2 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight depending on your goals. If you’re primarily focused on maintaining general health, aim for the lower end. Athletes and people doing regular strength training benefit from the higher range. Your activity level, recovery needs, and even your timing of protein consumption throughout the day all influence how effectively your body uses that protein. The quality of your protein sources matters too—pairing complete proteins with proper spacing throughout the day delivers better results than cramming it all into one meal.

Pro tip: Calculate your daily protein target by multiplying your body weight in kilograms by 1.6 if you exercise regularly, then spread that amount across 4 to 5 meals throughout the day for optimal muscle protein synthesis and sustained energy.

Different Protein Sources and Quality Ratings

Not all proteins are created equal. You could eat 30 grams of protein from chicken breast versus 30 grams from certain plant sources and experience vastly different results in your body. The difference comes down to amino acid composition and how well your body can actually absorb and use that protein. This is where protein quality ratings become your secret weapon for making smarter choices. Instead of just counting grams, you want to understand what you’re actually getting nutritionally. Your body needs all nine essential amino acids in the right ratios, and some protein sources deliver this complete package while others fall short.

Scientists measure protein quality using metrics like DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score) and PDCAAS, which evaluate how well your digestive system absorbs amino acids and how well those amino acids match your nutritional needs. Animal proteins like eggs, beef, and dairy typically score highest because they contain all essential amino acids in optimal ratios and are easily digestible. Plant proteins like beans, lentils, and nuts often have lower scores individually, but here’s the practical advantage: when you combine different plant proteins throughout the day, they complement each other’s amino acid profiles. For instance, pairing rice with beans creates a complete protein. Understanding protein quality metrics and digestibility helps you design meals that work harder for your fitness and wellness goals, whether you’re omnivorous or following plant-based nutrition.

Here’s what actually matters for your daily choices: prioritize high-quality protein sources that fit your lifestyle. Fish and poultry offer excellent quality with moderate calories. Eggs deliver complete proteins affordably. Greek yogurt and cottage cheese combine quality with convenience. For plant-based eaters, best protein sources for vegans provide strategic options to maximize amino acid intake. Processing can reduce protein quality, so whole foods generally beat heavily processed options. The practical strategy isn’t obsessing over DIAAS scores but rather rotating between different quality sources and combining complementary proteins. Your Dietium meal planning tools can help you track whether you’re hitting complete amino acid profiles daily.

Pro tip: Combine a high-quality complete protein source with a complementary plant protein at one meal (like grilled chicken with quinoa) to ensure you’re getting all essential amino acids while keeping meals interesting and sustainable.

Here’s how protein quality compares between common sources:

| Protein Source | Complete Amino Acid Profile | Typical Digestibility | Example DIAAS Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs | Yes | Very High | 1.13 |

| Beef | Yes | High | 1.10 |

| Greek Yogurt | Yes | High | 1.18 |

| Chicken Breast | Yes | Very High | 1.08 |

| Lentils | No | Moderate | 0.62 |

| Tofu | Nearly Complete | High | 0.91 |

| Quinoa | Yes | High | 1.04 |

| Almonds | No | Moderate | 0.40 |

Daily Protein Needs for Active Lifestyles

If you’re hitting the gym regularly, doing cardio, or training for any sport, your protein needs jump significantly above the sedentary baseline. Your muscles aren’t just sitting there during rest days—they’re actively remodeling themselves based on the stress you place on them during workouts. Without adequate protein, you’re essentially asking your body to build with insufficient materials. The difference between an inactive person and someone training seriously can be dramatic. Where a sedentary adult might thrive on 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight, an active person typically needs 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kilogram depending on training intensity and goals.

Your specific protein needs depend on what you’re actually doing with your body. Endurance athletes like runners and cyclists benefit from the lower end of that range, around 1.2 to 1.4 grams per kilogram, because their training focuses on aerobic adaptation rather than muscle building. Strength athletes and people doing resistance training need the higher end, roughly 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilogram, to support muscle protein synthesis and recovery. The type of training matters because different exercise modalities trigger different metabolic demands. Protein requirements for athletes vary based on training volume, exercise type, and individual recovery capacity. Your age also plays a role—older active adults might benefit from amounts on the higher end of the range to combat age-related muscle loss. Beyond the total amount, how you distribute protein throughout the day matters enormously. Spreading protein across four to five meals with roughly 25 to 40 grams per meal maximizes muscle protein synthesis better than loading it all at dinner.

Here’s where your individual factors come into play. If you’re training intensely five to six days per week, you likely need the full 1.8 to 2.0 range. Moderate training three to four times weekly suggests 1.4 to 1.6 is sufficient. Recovery from intense training demands adequate protein intake paired with sufficient calories overall—protein alone won’t compensate for undereating. Meeting your protein goals naturally becomes easier when you plan strategically rather than leaving it to chance. Consider your training schedule, body composition goals, and recovery needs when calculating your target. Dietium’s macro tracking tools help you monitor whether you’re hitting your personalized protein targets consistently.

Pro tip: Calculate your daily target by multiplying your body weight in kilograms by 1.7 if you train four to five times weekly, then divide that total by five meals to determine how much protein to aim for at each eating occasion.

Timing, Distribution, and Absorption Factors

Hitting your daily protein target matters, but how you spread that protein across your day matters just as much. Your muscles don’t suddenly wake up and synthesize protein because you ate 100 grams at dinner. Instead, muscle protein synthesis happens continuously throughout the day, triggered by adequate amino acid availability and exercise stimulus. The timing and distribution of protein intake directly influence how effectively your body captures those amino acids for muscle building and recovery. Think of it like filling a bucket with a hole in the bottom—you could dump the entire bucket at once and lose most of it, or pour steadily and capture more of what you need.

The science points to a consistent pattern: spacing protein intake evenly across meals optimizes muscle protein synthesis better than concentrating it into one or two large meals. Meal timing and leucine thresholds show that each meal needs roughly 2.8 to 3.0 grams of leucine, an essential amino acid that triggers the protein synthesis pathway. For most people, this translates to about 25 to 40 grams of quality protein per meal spread across four to five eating occasions. Age matters here too—older adults may benefit from slightly higher amounts per meal because their muscles are less sensitive to amino acid signals. Post-workout timing still carries importance, but not in the mythical “anabolic window” sense. Within a few hours after strength training, consuming 20 to 40 grams of protein provides amino acids when your muscles are primed to use them. The timing becomes less critical if you’re already distributing protein adequately throughout the day.

Absorption speed varies dramatically based on your protein source and how it’s prepared. Protein digestion and absorption rates change significantly depending on food processing methods. Whole eggs absorb slowly, releasing amino acids over several hours, while whey protein concentrate absorbs rapidly, spiking amino acid levels within minutes. Neither approach is inherently superior—they simply work differently in your system. Whole foods like chicken breast, fish, and legumes provide steady, prolonged amino acid release. Processed options like protein powder offer convenience and rapid delivery. The practical strategy combines both: use whole foods as your foundation and turn to processed sources strategically around workouts or when convenience demands it. Your digestive system, metabolic rate, and training stimulus all influence how much of that protein actually gets used versus passing through your system.

Pro tip: Space your protein intake into four roughly equal meals containing 25 to 35 grams each rather than loading 80 grams at dinner, and pair each serving with regular physical activity to maximize how much amino acids your muscles actually capture.

Risks of Too Much or Too Little Protein

Balance matters more than extremes. On one end, consuming too little protein creates real physiological problems that go beyond just failing to build muscle. Your body needs protein for immune function, hormone production, bone health, and countless enzymatic processes that keep you alive. When intake falls significantly below your needs, muscle wasting accelerates, your immune system weakens, and your body literally starts breaking down its own tissue for essential amino acids. On the opposite end, consuming excessive protein doesn’t transform you into a superhero either. Your kidneys don’t explode from high protein intake if you’re healthy, but unnecessarily high amounts do create extra metabolic work and can contribute to weight gain if those additional calories aren’t factored into your overall energy balance.

The risks of protein deficiency deserve attention because millions globally still face inadequate intake. Severe deficiency causes conditions like kwashiorkor and marasmus, characterized by muscle wasting, edema, and immune collapse. In developed countries, you’re less likely to hit these extremes unless you’re significantly undereating overall, but even moderate shortfalls accumulate over time. Older adults with consistently insufficient protein gradually lose muscle mass and strength, eventually affecting their ability to move independently. Athletes underestimating their needs will experience slower recovery, reduced performance, and higher injury risk. Health impacts of protein intake extremes show that deficiency creates more immediate danger than excess, but both represent problems worth avoiding. The key distinction is that deficiency is genuinely dangerous while excess is largely benign for healthy people without kidney disease.

Excessive protein intake carries minimal direct risk for people with normal kidney function. Your kidneys filter metabolic byproducts from protein breakdown just fine, even at doubled or tripled intake levels. The real concern with very high protein diets usually involves secondary factors: if your high protein sources also contain high saturated fat and sodium, those become the actual health risks, not the protein itself. Additionally, if chasing high protein means you’re overeating total calories, that extra energy gets stored as fat regardless of its source. Some research suggests potential links between certain types of high protein consumption (particularly excessive red meat) and chronic disease risk, but this reflects the entire dietary pattern rather than protein specifically. Consequences of excessive protein intake indicate that moderate excess protein poses minimal harm compared to deficiency risks.

Your practical target sits comfortably between these extremes. Aim for amounts aligned with your activity level and goals—typically 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kilogram for active individuals. This range sits well above deficiency concerns and below the point where excess becomes problematic. Prioritize high quality protein sources that aren’t loaded with saturated fat. Combine protein intake with overall balanced nutrition rather than obsessing over protein while neglecting vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats. Track your intake periodically using Dietium’s nutrition tools to ensure you’re hitting your target consistently without going overboard.

This table summarizes risks of protein extremes:

| Protein Intake Level | Main Risk Factors | Typical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Too Little (Deficient) | Immune weakness, muscle loss | Fatigue, slow recovery |

| Adequate (Optimal) | Supports health, muscle repair | Steady strength, good energy |

| Too Much (Excessive) | Added calorie load, kidney strain if pre-existing disease | Possible weight gain, no added benefit for healthy kidneys |

Pro tip: Calculate your minimum daily requirement using 1.2 times your body weight in kilograms, then verify you’re hitting that target at least five days weekly rather than obsessing over daily perfection or consuming dramatically excess amounts.

Master Your Protein Intake with Personalized Meal Plans and Smart Tracking

Understanding your optimal protein intake can be challenging with so many conflicting myths and numbers floating around. Whether you struggle to hit the right grams per kilogram or find it hard to balance protein quality and timing across your meals, the key is personalized guidance that fits your unique lifestyle and goals. This article highlights the importance of tailored protein targets and proper distribution for muscle health, recovery, and overall wellness.

Dietium makes it easy to put science-backed nutrition into practice. With the Recipians app, you get personalized meal plans and protein-focused recipe suggestions designed to optimize your daily intake whether you are an athlete or simply aiming for better health. Use Dietium’s smart nutrition and fitness calculators to track your progress, adjust your protein goals based on activity level, and monitor how different food sources contribute to your wellness. Don’t wait to transform your diet. Start integrating balanced protein intake into your routine today by visiting Dietium’s Recipians platform and make every meal count.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the optimal protein intake for active individuals?

Optimal protein intake for active individuals typically ranges from 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight, depending on training intensity and goals.

How does protein quality affect muscle building?

Protein quality affects muscle building because not all protein sources provide the same amino acid composition. High-quality proteins, such as animal sources, contain all essential amino acids in optimal ratios, while some plant proteins may need to be combined for a complete profile.

Why is timing and distribution of protein intake important?

Timing and distribution of protein intake are important because spacing protein across multiple meals—around 25 to 40 grams each—maximizes muscle protein synthesis compared to consuming it in a single meal.

What risks are associated with consuming too little protein?

Consuming too little protein can lead to muscle wasting, weakened immune function, and serious health issues such as fatigue and slow recovery due to a lack of essential amino acids necessary for various bodily functions.

Recommended

- Best Time to Eat Protein: Maximizing Muscle and Metabolism – Dietium

- Protein Intake for Weight Loss: Simple Guide for Success – Dietium

- Easy High Protein Meals for Every Lifestyle in 2025 – Dietium

- How to Meet Protein Goals Naturally: Step-by-Step Success – Dietium

- Best Protein Treatment for Natural Hair in 2025: Growth & Care | MyHair